At face value, the Chronicle of Higher Education’s 8 Things You Should Know About MOOCs, a data draw from the recent edX release of data, reads more like 8 Things You Already Know About MOOCs: MOOCs are populated by highly educated individuals, most registrants do not interact, registration is highly Western. Such tepid information makes the article feel like click-bait; anyone following MOOCs over the last 2.5 years could point to prior evidence of these facts the Chronicle article presents as novel.

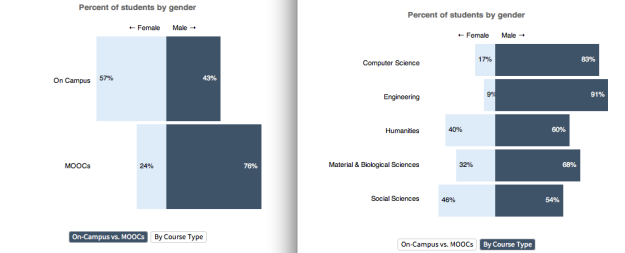

What I found most interesting was the graphic relating to the gender distribution fact: over 3/4 of edX students are male. Again, this is not novel information; the Penn survey in 2013 noted this, data further elucidated by New Scientist magazine. But the Chronicle presents the graphic by first showing gender breakdowns across American college campuses, where 57% of students are female.

It is a pretty stark difference to see a nearly 3 to 2 female to male majority on campus shift to 3 to 1 male to female in the world of MOOCs. One could argue that fewer women than men participating in MOOCs is not necessarily shocking; there are many articles on record showing the STEM field to be male-dominated (some sensational, others more tempered), so this data could be read to support a largely accepted happenstance. However, MOOC research (and EdTech research in general) is almost always instrumental by design, a form of A/B testing that abstracts the system from the environment and fails to account for political, cultural or social elements.

This is especially interesting when online education is viewed as related or deriving from distance education, a 150+ year old field of practice serving a marginalized population (usually those unable to attend traditional formal education due to distance, disability, or discrimination on the basis of race/gender/class). Why have MOOCs, long sold as a democratizing agent for global quality education, failed to deliver to such a population? Moreover, if the MOOC phenomenon is tied into the theory of disruptive technology (examples are numerous, but two here: I made such a case last week; also, Matt Candler includes Christensen in his must-read history of education book list at EdSurge), what untapped market does the MOOC serve if the existing market not only serves the historically marginalized, but does a much better job than the MOOC? The data in the graphs show the MOOC movement is dominated by men as well as fortified in geographic areas with strong ties to Western education systems (North America, Europe, South Asia). Read in this way, the MOOC is not an example of disruptive innovation; it would be more apt to consider it as an appendage of the status quo than an agent of disruption.

In America (and in many cases around the world) higher education not only grows but includes more first-generation students in its institutions, bringing to fruition a core tenet of the Enlightenment (opportunity for knowledge) bolstered by various public policy initiatives (Morrill Land Grant, Higher Education Act, GI Bill, etc). Yet the rhetoric of crisis continues, dissatisfaction grows, and the marginalized largely remain at a disadvantage to those traditionally with power. The crisis of education is a perpetual crisis, but the crisis is one of societal stratification as America’s crisis is not across-the-board. This gets at the heart of one of the most important issues facing the future of higher education today: rather than a narrow focus on the purpose of higher education in society, asking the question is educational technology offering unprecedented access to globalized and democratized education or is it answering questions of ease and economy that continue to limit the power and capital of traditionally marginalized individuals and groups?

When we view education as a narrative building from the first universities nearly 1000 years ago, the logical conclusion is to view events and precedents in the same way an author engages plot devices or character turns. Evoking the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard, this creates a grand narrative for society to engage, one of emancipation: society sought education for all of its citizens due to a belief that educated citizenry can best further the aims of society, and over 1000 years our view of education did not change but rather our view of citizen incorporated heretofore marginalized populations, culminating in various political changes around the world throughout the 1960s (seen in America through the Great Society) where policy provided the state more opportunity to assist citizens in emancipation. This changed in the 1970s as public policy pulled back on its social initiatives, to the point that in 2014 the Great Society is seen as a specter, a Golden Age that was unsustainable.

Many consider the resulting landscape to be the result of neoliberalism, an economic theory used by educators and cultural critics in largely pejorative terms to describe the deregulation of social services and subsequent privatization of said services. There is crossover between the neoliberal economic argument and today’s landscape of higher education, but the term is not apt for this education movement; the theory’s transition from economic to educational has not been smooth, and moving the theory from K-12 education (a space where privatization has come via government intervention in public-private partnership) to Higher Education (where government intervention remains slight though looks to increase and in unique ways as evidenced by the partnership between Starbucks and Arizona State University). Neoliberal arguments are fact-based applications of theory but fail to provide organization for those affected with more than a wish to return to said grand narrative. This approach has largely failed, potentially because there is no grand narrative to return to and there perhaps never was a grand narrative to start with.

We are in a space and time where more first-generation college students are enrolled in degree-seeking programs, but the aim of higher education has shifted from a notion of happy and effective public and private citizen with intangible benefits to a discussion of job training, career placement and lifelong learning. Back to Lyotard, he notes in his 1984 work The Postmodern Condition that higher education’s purpose in society has shifted from visionary to functionality; the system sees value in creating operators of its devices and experts in the system rather than those who can re-imagine and challenge, remodel or alter the system. The opening of higher education to all people (in America it is since the 1970s that education enrollments have skyrocketed) was to some extent liberatory but also it was pragmatic; in Jürgen Habermas’ The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, he notes the great lengths in which power has worked throughout history to facilitate spaces of access while never relenting privilege or advantage. College as a gateway to a better life is replaced with college as a gateway to a better job, one perhaps with better pay or better benefits but often at a personal and societal cost. We are in a quagmire of competing narratives about the past, present and future of higher education and its purpose, and all of the narratives are based on a true story but none of them are true.

Contemporary learning theory tells us that learning happens best when it is situated in an environment and contextualized for that space. Postmodern theory asks us to push away the notion of a grand narrative and rather build local narratives in situated, contextualized environments. The MOOC movement promises us globalized and democratic educational opportunities, ones which can scale learning and provide efficiency in a market where some see issues in the structure’s existing capacity: there is a solution on the horizon, one which Everyman can manage if they harness their grit, tenacity and gumption. Critics continue to attack the MOOC and point out its inefficiencies as if acute realization will result in more than a mass of MOOC-as-Hype-Cycle articles. Awareness is not in itself a response; otherwise, the disparity between male and female MOOC registrants would result in significant changes to the product’s features. Rather, awareness is power to create and promote alternative and change, not in the avoidance of MOOCs or other EdTech wares, but in utilizing the technology of the day to alter and transform individuals, networks and communities.